A plan to help youth experiencing suicidal ideation, as well as their parents or caregivers, had to pivot when the pandemic started.

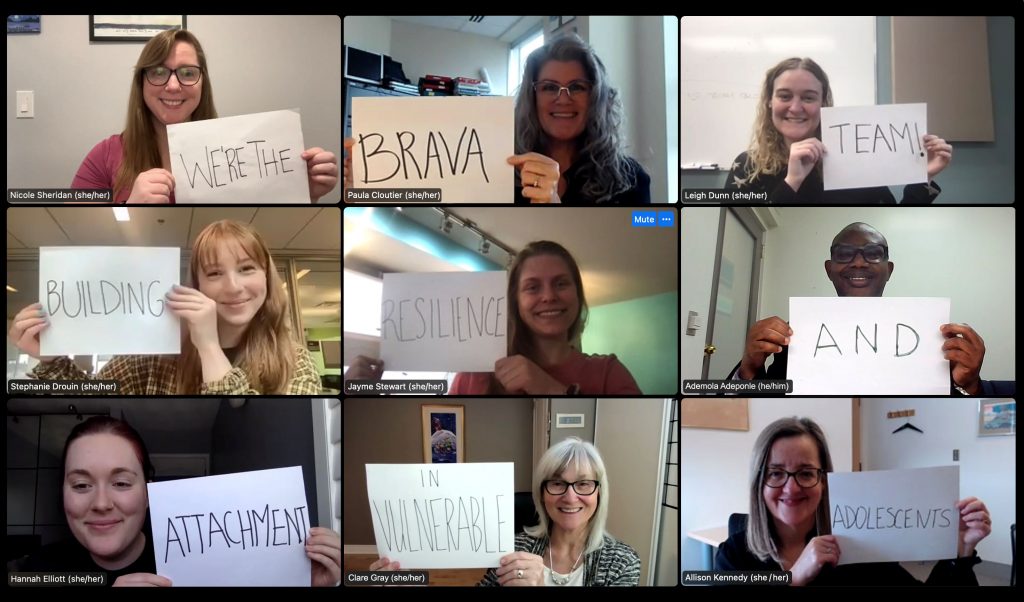

The BRAVA team. Top row: Nicole Sheridan (research coordinator), Paula Cloutier (co-principal investigator), Leigh Dunn (research assistant); middle row: Stephanie Drouin (research assistant), Jayme Stewart (research assistant), Ademola Adeponle (co-investigator); bottom row: Hannah Elliott (research assistant), Clare Gray (co-principal investigator), Allison Kennedy (co-principal investigator).

It started with a good idea — to offer adolescents who were thinking about suicide, as well as their parents or caregivers, prompt access to group therapy. And to do a research study to understand how well the intervention worked. But, for a group of researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa, there were many hurdles along the way. In facing these, they had to exemplify the connection and resilience that they aim to build in the adolescents.

Today, the research is almost complete, with only a few more participants needed before the research team can compile their data. But there were points when “we had to go back to the drawing board,” says Dr. Allison Kennedy, a clinical psychologist and one of three principal investigators on the research project, called “Building Resilience and Attachment in Vulnerable Adolescents” (BRAVA).

The Mach-Gaensslen Foundation of Canada was one of the funders of the research, investing $90,000 from 2012 to 2014 and $225,000 from 2018 to 2020.

Dr. Ian Arnold, the vice-chair of the foundation, notes that, “Psychiatry is one of three areas mandated for research funding by the Foundation’s founders, Vaclav F. Mach and Dr. Hanni Gaensslen. The BRAVA research program is an excellent example of a scientifically based research program with methodologies that can be widely applied and with outcomes that provide long-term benefits for adolescents and their families.”

But that excellence was hard won. While it’s common for research on real-world patient interventions to adapt as it proceeds, this research had to deal with a huge challenge — an unexpected pandemic that moved the intervention from in-person to online. And it happened just when the team was planning to start a major study.

Building BRAVA

When the pandemic lockdown hit, many years’ work had already gone into the intervention and research plans by Kennedy and the team — co-principal investigators Dr. Clare Gray and Paula Cloutier, four co-investigators, research coordinator Nicole Sheridan and several research staff.

The principal investigators had started the project in the early 2010s, explains Kennedy. “I was doing urgent mental health assessments for young people with suicidal ideation,” which means thoughts or ideas about death and suicide. “I would see them within a week of their presentation to the emergency department. Some of them they would be much better within a few sessions.” She talked with Gray and Cloutier about getting these youth and their parents or caregivers into an intervention very soon after they visited the emergency department. “And BRAVA was born,” she says.

First, the team developed a group therapy program based on recognized forms of psychotherapy that can help people thinking of suicide, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy. Separate groups were offered for youth and for their parents or caregivers. Each group had six sessions on skills to help participants improve their connection to others and resilience. But participants can join in at any session, so there is no delay in starting to participate. The researchers also had to prepare a detailed protocol for the research they were planning.

They first tried the program to ensure it was feasible and acceptable to youth. They then did a feasibility study involving 10 families in 2010, “and we learned what would make it better,” Kennedy says. She says the program is for youth with mild or moderate suicidal ideation, which means they have thought about suicide but can manage their safety, at least with support. Youth with more severe suicidal ideation need individual support.

The researchers then wanted to launch a study comparing a therapy group with a control group that would not get the therapy, but patients balked. “It failed miserably. Once kids found out there was a 50 per cent chance of not getting involved, some didn’t want to participate.” Others who started in the control group did not complete their participation.

Kennedy says this was the first time, but not the last, the researchers had to rethink their plans. Instead of a controlled study, they did a study of how participants were doing before and after the therapy, so they were all included in therapy. This first study showed that therapy reduced suicidal ideation significantly, as well as parents’ or caregivers’ stress levels. Results were published in a peer-reviewed journal.

For a larger randomized controlled study — which provides much stronger evidence of how effective the intervention is — the researchers changed how the control group works. They offer participants in the control group some forms of support. These consist of helpful weekly text messages with coping tips and reminders of crisis resources. “There is some evidence from other researchers that this has some positive impact,” explains Kennedy. And youth and parents or caregivers in the control group can join the BRAVA program later.

The research team also reached out to other departments of the hospital and to other doctors and programs, beyond the children’s hospital, to recruit youth thinking about suicide. These included the Youth Services Bureau, the Ottawa Community Pediatricians Network, the Manotick Medical Centre, and 1Call1Click.ca, an integrated system for child and youth mental health and addiction care that links together existing services in eastern Ontario.

Pandemic pivot

Everything was in place when the pandemic forced the team to pivot.

The groups moved from in-person to virtual. Researchers did a pilot study with six families to see how the virtual sessions were working. This led to some changes, such as shortening some of the content to teach youth.

“They couldn’t cope with as much virtually,” says Kennedy. The team also ensured that slides presented virtually “spoke for themselves,” with clear content and appealing graphics.

When the study launched with virtual group therapy, the response was positive. “We wondered, with the virtual format, would participants get a sense of interpersonal connection from other participants? The feedback is that they did,” says Kennedy. She says the virtual format has also allowed participants from other towns and cities in the region to participate without having to travel.

The study is expected to conclude soon. Although the data cannot be analyzed until the study is complete, there are already signs of success. “I see great value in BRAVA,” says Kennedy. “I see that the youth stick with it and don’t drop out. That’s pretty good on its own.” Paula Cloutier adds, “Caregivers report feeling supported and less alone. They also report gaining new knowledge and skills that they find helpful in understanding and responding to their youth’s needs.”

Analysis will show whether BRAVA changes suicidal ideation in youth, measured through standard psychometric questionnaires. The researchers plan to follow up with youth for several months, asking them to complete questionnaires and looking at their medical records “to see how they are doing.”

In addition to publishing research results, the BRAVA research team has mentored many young staff members at the children’s hospital who have gone on to advance their education or careers.

What is the future for BRAVA? To this point, it has been offered as part of a study. The challenge is to make it a service regularly offered to youth with suicidal ideation and their parents or caregivers. It could be made available in the community as well as through a hospital. For example, Kennedy has adapted the content for a program called “Step Up, Step Down” at the Ottawa Youth Services Bureau. There are benefits to either in-person and virtual formats, so both may be available in future. Once the study is complete, the researchers will focus on making BRAVA content available so it can be adopted in other communities across Canada to help youth embrace a future without self-harm or suicide.

See All News